Vocabulary acquisition is crucial for second and foreign language learning, as emphasized in our last article. We need to grow and cultivate our vocabulary to progress in our language studies, but how does it actually happen? When can you say you have successfully learned a new word? This article will examine these questions, which are worthy of consideration – not just in a theoretical sense, but because a basic understanding of the vocabulary acquisition process is highly important for establishing efficient vocabulary instruction, assessment and learning strategies.

At first glance, vocabulary acquisition might seem likea simple matter: you either know a certain word or you do not. However, as with so many other language learning related issues, we are actually dealing with a rather complex process. The linguist Norbert Schmitt describes this complexity by stating in his 224-page book that “(A)n adequate answer to the single question ‘What does it mean to know a word?’ would require a book much thicker than this one”. However – in spite of the complicated nature of vocabulary learning and the fact that its mechanics still remain somewhat mysterious – there is one thing we can be sure of: at least when it comes to adult language learners, words are not learned instantaneously. Instead, they are gradually acquired over a period of time through numerous exposures. (1)

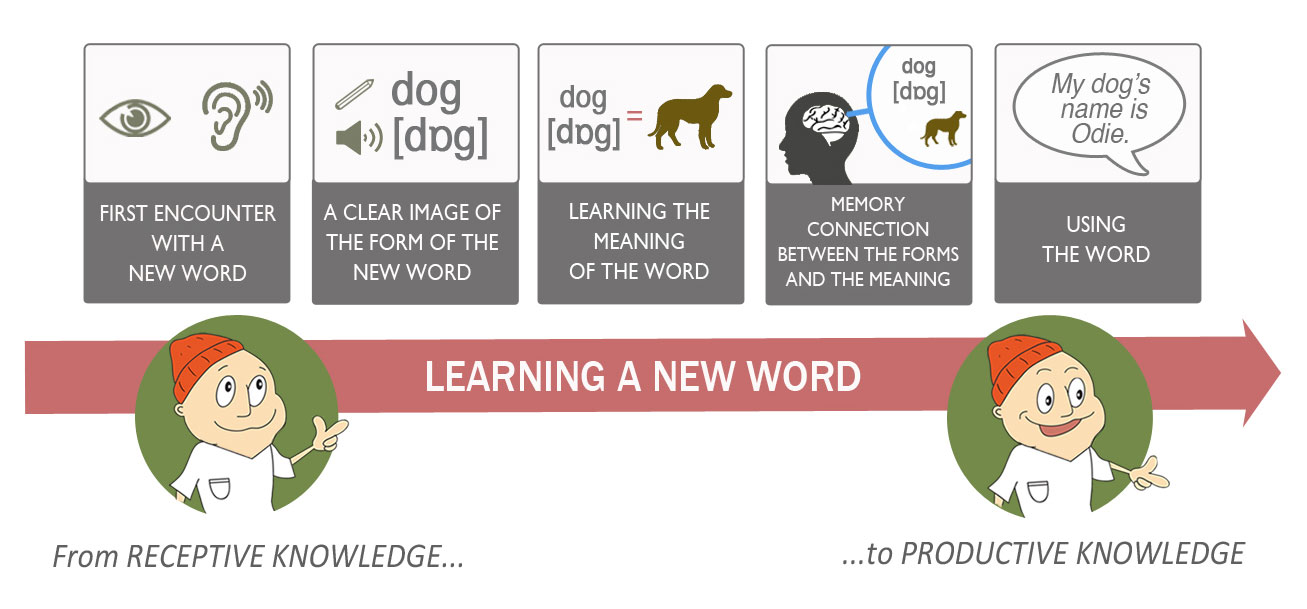

Five steps can be identified in this process (2):

(1) First encounter with a new word

(2) A clear image of the form of the new word – either visual, auditory or both

(3) Learning the meaning of the word

(4) Making a strong memory connection between the form and the meaning

(5) Using the word

In order to move from not knowing the word to being able to use the word correctly, a language learner must successfully go through all of these steps. It is not possible to use the word accurately if the spelling, pronunciation and meaning(s) of the word are not properly learned. On the other hand, if a learner fails in making a long-lasting memory connection between the form and the meaning (step 4), the efforts made in the first three stages will be useless. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that, to make this process as efficient as possible, a learner should receive instruction and choose learning strategies that are pedagogically designed and optimized to meet the specific needs of each of these stages.

The same gradualness can also be examined by dividing the vocabulary knowledge into receptive and productive knowledge (3). Receptive vocabulary knowledge is commonly defined as the ability to recognize the form and recall the meaning in listening and reading, while productive knowledge refers to the ability to retrieve and produce the correct spoken or written form of a word in the target foreign language (4). The learning of the word usually progresses from knowing the word receptively to knowing the word productively (5): normally we learn to recognize and understand a word first, and only afterwards how to use it. Although this causality can be debated (6), it is difficult not to agree that “a word that can be correctly used should also be understood by the user, when heard, seen or both” (5).

While acquiring productive knowledge with WordDive, you will also learn plenty of other words in a receptive manner (the words in examples and descriptions forming context for the words in focus). On the other hand, learning words receptively does not necessarily lead to productive knowledge. Therefore, we encourage you to focus on the productive aspect of vocabulary learning – having the words in your long term memory and being able to use them when speaking or writing. This is the fastest way to learn to use a new language as well as to learn more while using it.

Lastly, besides the quantitative dimension of vocabulary, there are qualitative factors that should be considered: it is not only the size of the vocabulary (the number of words known) that matters, but also its depth (how well a particular word is known). Most researchers agree that vocabulary knowledge is not all-or-nothing phenomenon, but involves degrees of knowledge (5), and should be seen as an incremental process: a continuum from not knowing to rich knowledge of a word’s different meanings, its relationship to other words, and its extension to metaphorical uses (7).

Next month we will continue to explore the word learning process, but this time from a cognitive point of view. As acquiring new vocabulary is not just about learning, but also about remembering, we will concentrate on the role of memory in vocabulary acquisition.

Happy language learning, everyone!

Timo-Pekka

WordDive team

References and Further Reading:

(1) Schmitt, Norbert (2000). Vocabulary in Language Teaching. Cambridge University Press.

(2) Hatch, Evelyn & Cheryl Brown (1995). Vocabulary, Semantics, and Language Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(3) See e.g.: Mondria, Jan-Arjen & Boukje Wiersma (2004): Receptive, productive and receptive + productive L2 vocabulary learning: What difference does it make? − Vocabulary in a Second Language; 79−100.

Pinner, Richard S. (2009). Understanding Meaning: Defining expectations in vocabulary teaching. King´s College London.

Zhong, Hua (2011). Learning a Word: From Receptive to Productive Vocabulary Use. University of Sydney.

(4) Nation, Paul (1990). Teaching and Learning Vocabulary. Newbury House, New York.

(5) Laufer, Batia (1998). The development of passive and active vocabulary in a second language: same or different? Applied Linguistics, 19(2), 255-271.

(6) E.g., Warning, Rob (2002). Scales of Vocabulary Knowledge in Second Language Vocabulary Assessment. Appeared in Kiyo, The occasional papers of Notre Dame Seishin University.

(7) Beck, Isabel & Margaret McKeown (1991). Conditions of vocabulary acquisition. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research, 789-814. New York: Longman.

A mighty mix of language learning professionals, engineers, designers, user interface developers, gamers and psychologists.

3 Comments

[…] acquisition is essential for language learning, but we also know that learning words is not a simple task. Given this, it is quite understandable that many language learners might be asking how many words […]

“It is not possible to use the word accurately if the spelling, pronunciation and meaning(s) of the word are not properly learned.”

This surely isn’t entirely true. Illiterates, among others, can use words with total accuracy and appropriacy without knowing how to spell them.

Hi Joe,

Thank you for your comment!

You are correct about the illiterates. However, we see language skills as a completeness that include reading, writing, listening, speaking and understanding. In this sense you have to able to spell a word in order to use it accurately.

Best Regards,

Iida

WordDive-team